Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

What comes to mind when you hear the phrase differentiated instruction?

Does it feel like a buzzword? A nice idea in theory. But not something that can work in a real classrooms?

Some educators oppose differentiated instruction on principal. To them, differentiation means lowered expectations, grade inflation, and “giving every kid a trophy.”

I know this because I was one of those educators. I’m a bit ashamed to admit it, but at some point in my teaching career, I’ve said (or at least thought) all of these things.

But the real reasons I resisted differentiated instruction were much more human. I was tired and overwhelmed. I had lessons to plan and papers to grade.

I didn’t have time to examine my educational philosophy. But eventually, I came to realize that differentiated instruction is an essential teaching practice.

The importance of differentiated instruction is hard to overstate. But here goes: if you’re not differentiating, you’re not actually teaching.

Once, while giving a presentation on differentiation, a teacher called out to object. “It’s my job to present the information. It’s the student’s job to learn it.”

“So,” I asked, “If you explain an idea, and no one in the class understands it, you’ve done your part.”

“Yes I have,” he affirmed.

But I disagree. Setting such a low bar for effective teaching is dangerous. A computer can present information, assess understanding, and give feedback. All more efficiently than we can. And there are plenty of ed reformers who would happily replace us all with computers.

The reason teachers can’t be replaced is because, unlike computers, we can respond to our students’ intellectual and social-emotional needs.

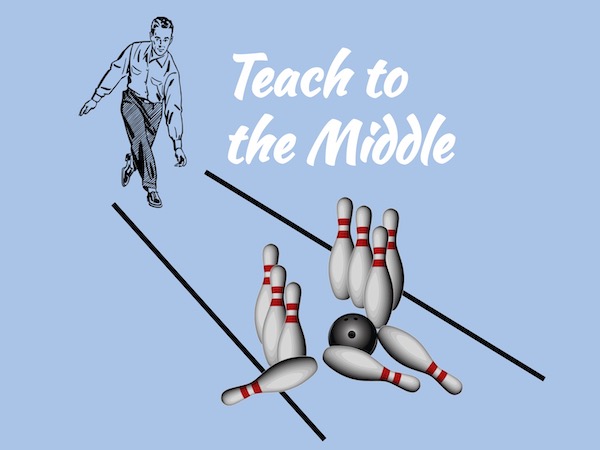

Many teachers are familiar with the phrase teach to the middle. This is the classic, non-differentiated approach. Find the “average” student, and teach to their needs. It will be too slow and simplistic for one-third of the class. And it will be over the heads of another third. But if you’re lucky, you might reach the middle third.

Many teachers are familiar with the phrase teach to the middle. This is the classic, non-differentiated approach. Find the “average” student, and teach to their needs. It will be too slow and simplistic for one-third of the class. And it will be over the heads of another third. But if you’re lucky, you might reach the middle third.

This model ensures that at least two-thirds of your students are disengaged. Differentiated instruction helps you to reach them.

Once I began to embrace differentiation, I noticed the benefits almost instantly. My students were more engaged, and their performance improved across the board.

And while some educators feel that one-size-fits-all learning prepares students “for the real world,” it’s quite the opposite. In the real world we’re not all expected to do, or know, the same things. I never learned how to install an electrical box or perform heart surgery. But I can still be successful by focusing on my strengths and interests.

There is no shortage of strategies that support differentiated instruction. But you don’t need to master them all to be effective. In fact, the most important step is simply understanding that differentiation matters.

The next is to know what differentiation is. And what it is not.

Have you ever completed a learning styles inventory? These questionnaires seek to identify a student’s learning style (visual, auditory, or kinesthetic), under the premise that students learn best when teaching matches their preferred sense. Though the idea has been disproven for decades, many teachers still confuse differentiation with learning styles.

Others believe that differentiation means ensuring diverse learners all reach the same outcome, at the same time. This belief drives some teachers to give up on differentiation entirely, since they eventually realize it’s impossible.

Simply put, differentiation means adjusting how we teach, to meet the needs of our students.

The term, differentiated instruction, was coined by Carol Ann Tomlinson in the 1990’s. But educators had already been exploring the concept for decades (if not centuries). A 1953 issue of Educational Leadership, contained an eye-opening article called Adjusting the Program to the Child, which highlights just how persistent the challenge of differentiated instruction has been.

In addition to coining the term, Tomlinson identified four types of differentiation: content, process, product, and environment. Each form of differentiation addresses a unique learning need. Teachers should be familiar with all four, so they can pick the right strategy for the right situation.

Content differentiation simply means changing what students learn to match their readiness. But while it’s the easiest to explain, it may be the hardest to execute in a real classroom.

Teachers have upwards of 30 students in a classroom at a time. And we are required to ensure that each student masters the standards for our subject and grade level.

But even in traditional classrooms, there are ways differentiate content either by topic or by level.

If a 6th grade student struggles with fractions, we can’t just say “tough luck, that was a 3rd grade standard.” We need to address the 3rd grade content before the student can master 6th grade topics like ratios and algebraic expressions.

Matching content to student need was almost impossible 20 years ago. But advances in adaptive learning technology now make it relatively easy. A personalized learning approach uses technology to match instruction with students’ identified needs.

We can also differentiate content by allowing students to choose the topic, while keeping the standard consistent. One student may create a history presentation on the French Revolution, while another studies The Middle Passage. Both students can still develop the relevant research, writing, and public speaking skills, but the content is differentiated to match their interests.

These approaches can be used even in traditional classrooms. In progressive settings, students can break down their grade level standards, and create a plan for how they will master them over the course of a unit or course.

Taking it farther, in theory we could differentiate content entirely. This would probably be the most authentic form of schooling. Students would follow their interests. Rather than mandating core content, they could focus on coding, ballet, entrepreneurship, or whatever they wanted to learn.

In addition to changing what we teach, we can also modify how we teach. This is known as differentiation by process.

One student may read about a subject, while another listens to a lecture, and a third watches a video. Other students may learn best in collaborative groups.

To differentiate by process, we don’t have to offer every option in a single class. We can lecture one day, assign work on an online platform the next, and complete an inquiry-based learning task the third.

One form that gets a lot of attention is scaffolding. Scaffolds are teacher-provided supports that help students access content they could not master on their own. The term was coined by Jerome Bruner, and largely based on the research of Lev Vygotsky, such as his Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

While scaffolding is an important instructional strategy, it is often misunderstood. When students are on the edge of understanding, extra supports are useful.

But scaffolding can be used as an excuse not to allow students to learn content at the appropriate level. If a student reads on a 3rd grade level, we can’t scaffold them into reading a 7th grade book. If they are struggling to multiply whole numbers, we can’t scaffold them into multiplying fractions.

In these cases, it is necessary to differentiate the content. This still leads, eventually, to grade level competency. But differentiated instruction demands we honor student differences. Not forcing students to all become competent at the same time.

When scaffolding is done correctly, a student will still demonstrate competency when the scaffold is removed. When we overscaffolding, they only appear competent until the scaffold is removed.

A third way to differentiate is by altering the way we assess student learning.

If we want a student to understand and describe the factors that led to the French Revolution, we can assess their understanding with a multiple choice test. But what if they struggle with reading? What if they make a few lucky guesses?

The purpose of differentiating products of learning is to ensure that our assessment doesn’t obscure a students’ actual understanding.

A student could just as easily demonstrate their understanding with a presentation or an essay. A one-on-one conversation may even tell me more about their understanding of historical cause and effect.

One way to differentiate products is to combine assessment types. On a unit test, I will combine a few multiple choice and fill-in-the-blank questions, with open-ended paragraphs, or even drawings and diagrams.

You can also let students choose how they will demonstrate their understanding. The key is to ensure their product actually demonstrates understanding. A collage of Napolean and guillotines is not a demonstration of understanding.

The fourth type of differentiated instruction involves modifying the learning environment. This may include changes in seating arrangements, tone of voice, brightness of lights, etc.

The idea is to elevate the importance of student comfort and empowerment.

And while I wholeheartedly support the importance of such social-emotional considerations, it seems a bit out-of-place as a form of differentiation.

For one, many of the ways we differentiate the “environment” already fall under other categories. If we rearrange our seating from rows into pods, we’re hopefully doing so to support collaborative learning. As such, it would be an example of differentiation by process.

It also seems like student empowerment and using a kind tone of voice would benefit all students. I’d find it hard to believe that some students learn best in environments where teachers bark orders and don’t value student voice.

I guess it’s possible some students learn best with bright lights, while others prefer mood lighting. But few teachers are able to section their classrooms into quadrants of varying luminosity.

No matter how you choose to differentiate your instruction, it’s unlikely to be easy.

That’s because schools were not designed to give each student a unique learning experience. Many of the structures in place, from high student-teacher ratios to standardized tests, compel educators to treat every student in the same way.

As such, effective differentiation often requires changes at the school and district level, not just in individual classrooms. Teachers need flexible curriculum plans that allow them to respond to formative asessment. Schools need to support personalized learning with technology resources, schedules, and school-wide systems for organizing student data.

The Three-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools and districts implement the changes necessary for differentiated instruction. It balances the three bridges of learning, each of which has its own instructional methods and metrics of success.

Content Coverage: Effective curriculum planning ensures grade level content is covered, while still allowing time for personalization and inquiry. Success is measured traditionally, with percentages and unit tests.

Personalized Learning: Adaptive technology matches instruction to students’ individual needs. Success is measured in years of growth.

Inquiry-Based Learning: Students engage in problem-based and project-based learning to develop conceptual understanding and social-emotional skills. Success is measured with rubrics and reflections.

Traditional schools rely almost entirely on a content coverage approach, which makes differentiated instruction difficult.

Three Bridges schools balance all three instructional models, and measure success differently for each. To learn how your school can make differentiation easier and more effective, read more about The Three Bridges Design for Learning.

Even if your school hasn’t yet adopted the Three Bridges model, there are many ways to differentiate successfully.

The first step is to simply buy in to differentiated instruction. Recognize that every student has different needs. And accept that your role as an educator is to support those needs, not to rate and sort students based on performance.

There are a number of simple, informal ways to understand our students’ needs. Coaching conversations, surveys, and student goal-setting can help you better understand student perspectives on their learning experience.

Gathering and interpreting data is important for meeting students’ academic needs. Automated platforms make this easier, but good classroom assessments do this as well.

But data alone is not enough to differentiate. Unless your curriculum plans [link] allow you the flexibility to respond to formative assessment, the data is of limited value.

Whatever your goals are for differentiating instruction, Room to Discover can help. Our online instructional coaches work with educators to help you define and reach your goals.

And you can learn skills to effectively differentiate instruction in our upcoming online workshops for educators [link]. We also offer private workshops [link] and conulting [link] for schools and districts.

The good news is that you’ve already taken the first step. By taking the time to learn about differentiated instruction, you’re already benefiting your students. If you’d like to better understand your own strengths as an educator, download our free Guide to Reflective Teaching. It includes self-assessments, goal-setting activities, and success stories from other reflective teachers.

GET YOUR FREE GUIDE TO REFLECTIVE TEACHING

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Does the Danielson Rubric improve teaching? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, it’s a rubric, not a training program. But…

Effective curriculum plans are built by engaging teachers in a collaborative, school-based process. Getting a head start before summer break is key.