Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

If you’re one of the millions of educators shifting to virtual teaching, you know how challenging it can be to motivate students online.

This difficulty doesn’t just affect teachers. Staring at screens all day has left many students frustrated and unmotivated. And when students can’t get their work done independently, the burden shifts to parents.

The result is that almost no one is happy with online learning. We all feel like we’re working more and accomplishing less.

If we really want to motivate students online, we need a new approach. That means looking critically at what we did before online learning, and asking ourselves three questions: ‘What worked?’ ‘What didn’t?’ and ‘What now?’

Even before the pandemic, our ability to motivate students in school was mixed, at best. Several studies have shown student motivation decreasing with each year they attend school.

The main reason is our overuse of extrinsic motivators in schools. Extrinsic motivation describes motivation that comes from a desire to to receive a reward or avoid a punishment. It doesn’t matter whether we actually want to do the thing.

This type of “motivation” is also known as behavior modification, because the goal is to modify behavior, not mindsets. I actually wonder whether incentive-seeking should even be considered motivation.

I prefer to think of extrinsic motivation as ‘management,’ rather than motivation. When I’m working for external rewards, I’m usually thinking about the reward. I’m not feeling that internal drive that comes with real motivation.

Genuine motivation comes from within. Also known as intrinsic motivation, it arises when we enjoy the work we do. It can also come from a belief that our actions are in our long-term best interest, or that we are making a positive contribution to society.

Just because rewards and punishments aren’t “true motivation,” doesn’t mean they don’t play a role in a healthy motivational strategy.

Whether teaching online or in person, we should rely on a range of strategies to motivate our students. Each strategy has its benefits and limitations.

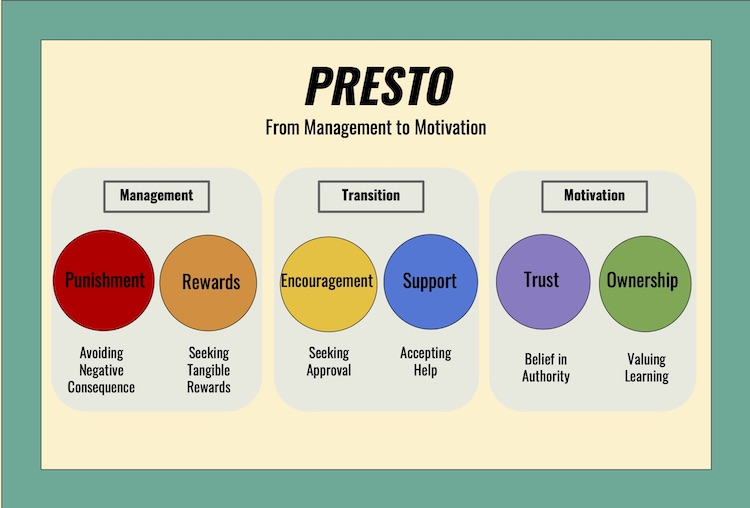

On the one end are management strategies. These are the punishments and rewards we use to compel students to follow directions, pay attention, and complete their assignments.

Punishments and rewards can be incredibly effective. But we must use them with caution. These strategies often create unintended consequences. And, they offer diminishing returns over time.

On the other end are motivational strategies, which emphasize trust and ownership. These strategies offer long-term benefits. But they are difficult to achieve, especially if your students are accustomed to working for external rewards. (And whose aren’t?)

In the middle are the transitional strategies, encouragement and support. These are especially useful when student ownership and intrinsic motivation seem out of reach.

Together, these strategies comprise The PRESTO System, a student-centered approach to classroom management. The PRESTO strategies are a spectrum, not a sequence. The idea is to balance the use of all strategies, gradually nudging our students to be intrinsically motivated.

We all want our students to be motivated by a love of learning. But the reality is that most of the ways we motivate students consist of rewards and punishments.

There are the obvious rewards, like candy and homework passes. And obvious punishments, like detentions and phone call homes.

But the most common incentives are grades. We like to think that grades are there to “help students understand their progress.” But for students, high grades feel like a reward. And low grades feel like punishment.

And there’s no denying the real-world consequences of grades. Grades determine what school students go to, who gets called on stage for academic prizes, and how much they’ll earn in their future careers.

Before I receive a barrage of angry emails, I’m not saying we should use grades to punish students. Lowering a student’s grade for behavior issues is counter-productive.

I’m saying that grading already functions as a reward and a punishment. Whether we like it or not. So let’s just accept that, at the current moment, it’s unrealistic to avoid management strategies entirely. They are the most powerful ways we can change student behavior in the short term.

But understand their limitations. Many educators believe that eventually, extrinsic rewards lead to intrinsic motivation. But the opposite is actually true.

Over time, incentives gradually lose their effectiveness. What’s worse, the use of incentives actually decreases intrinsic motivation.

And eventually, students look for ways to receive rewards (or avoid punishments), without meeting our expectations. If you’ve ever had a student copy a homework assignment or cheat on a test, you understand how that works.

For incentives to work, we can’t just dish out rewards and punishments whenever our students seem unmotivated. We should put systems in place beforehand, focusing on three areas: behaviors, incentives, and communication.

First, distinguish desired from undesired behaviors. For example, “lateness” and “missing assignments” are technically not undesired behaviors, as they describe something the student is not doing. Arriving on-time and completing assignments would be the desired behaviors.

Interruptions, insults, and academic dishonesty are active, undesired behaviors.

Once you identify desired and undesired behaviors, think of objective ways to measure them. If you want to reduce interruptions, come up with acceptable and unacceptable numbers of interruptions per class. If you want students to arrive on-time, figure out how many minutes of class they can miss a week before facing a consequence.

Next, make a list of things your students like, and a list of things they dislike. Then, circle all the ones that you have the power to give to them or take from them.

*Educators who struggle with classroom management often have a hard time making such a list. It’s a sign that they need to learn more about their students’ interests. This can be a great opportunity to ask them directly about their likes and dislikes, or conduct a survey.

The circled items on your list are your incentives. Rewards are effective for reinforcing positive behaviors, and punishments are best at reducing undesired behaviors. Punishing students for what they fail to do, or rewarding them for avoiding bad behavior both tend to backfire.

Since we can’t motivate students online with candy or detentions, it can be challenging to find the right incentives.

One approach is to build-in free time or fun time into the week. Then, reward students by letting them pick the music or the activity for the down time. And make participation conditional on good behavior. Another approach that works well online is the stopwatch strategy.

Once you identify your target behaviors and incentives, communicate your expectations clearly and consistently.

This means being very specific about what we want and how we’ll measure it. Avoid generalities like, “if you’re good, you’ll get to play a game on Friday.”

Instead, say something like “If you have completed all assignments for the week, you can participate in Friday’s game — unless you have three or more behavior warnings that week. The student with the most Dojo points can pick the music we listen to.”

It’s important that communication is ongoing. Once we set expectations, students need to know where they stand along the way. No one should be surprised if they miss out on “Friday fun day.”

We should also follow-up with students after assigning a punishment. Remind them why they received the punishment, assure them that it’s not personal, and let them know you believe they can do better going forward.

This limits the degree to which punishments erode our student relationships.

The transitional strategies ease the transition from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation. Assuming that rewards and punishment will lead to real motivation is just wishful thinking.

But by combining management strategies with encouragement and support, we really can help students take ownership of their learning.

There is a subtle, but important difference between rewards and encouragement. Rewards have tangible value. But we can encourage the behaviors we want (and discourage those we don’t) simply by expressing approval or disapproval.

Encouragement can be as simple as telling a student they did a great job. Or using “ the look” when they need to settle down.

We can encourage with tools like behavior charts and ClassDojo. But the minute we attach something of value (candy, grades, extra recess), these tools are no longer encouragement. They become rewards.

The difference is important. Research has shown that tangible rewards significantly reduce intrinsic motivation. But when students receive encouragement without rewards, there is no reduction, and possibly an increase, in motivation.

What’s more, tangible incentives are effective at getting people to complete simple, repetitive tasks. But they actually decrease our ability to think creatively and problem-solve.

So if we want our students to stock shelves, reward away. But if we want them to think creatively and conceptually, we need a less transactional approach.

Since we have fewer rewards and punishments when teaching remotely, encouragement is particularly useful for motivating students online. The biggest challenge is making time for small group or 1-on-1 sessions — it’s hard to encourage students effectively in a 25-seat videoconference.

The strategies covered so far address what we expect from our students, and how to get them to meet our expectations.

To provide support, we must consider the ‘why,’ as well. Why aren’t they meeting expectations? Are the expectations reasonable? Are they really trying? Could they meet our expectations if we gave them a boost?

Teenagers, especially, are terrified of being seen as incapable. Behavior that appears defiant may actually be a cover for a lack of confidence.

This is the opposite of the “no excuses” approach that has been adopted by some charter networks. In these schools, it doesn’t matter why students are struggling. That’s their problem.

There is a time and a place for a no excuses approach. When students are being willfully defiant or deceptive, negotiating or lowering our expectations can actually reinforce their negative behavior.

But we often assume students are unwilling, when in fact, they are unable. It can be hard to tell the difference. Teenagers, especially, are terrified of being seen as incapable. Behavior that appears defiant may actually be a cover for a lack of confidence.

There are two ways to support students in meeting our expectations. We can modify the expectations, or find way to help them meet them.

In recent years, modified expectations have fallen out of favor. Some people believe that it amounts to “giving up on our students,” or “causes them to fail.”

This belief is based on some very real research proving that teacher expectations can influence student performance. But that does not mean we shouldn’t modify expectations to meet students’ needs.

I compare it to shopping for pants. Let’s say I find an amazing pair of jeans with a 30” waist. I ask my wife if I should buy them. What should she reply?

The people who oppose adjusting expectations would say “A.” Never mind that I’ll hurt myself trying to put these jeans on, and will split them in half in the process. These folks seem to think that lowering expectations amounts to giving up on me entirely.

“B” is clearly the best answer. We can be both aspirational and realistic with our students. When we ask them to read books or solve math problems that are over their head, we are causing them real pain. No less painful than trying to wear jeans that are 4 sizes too small.

And squeezing into those jeans doesn’t actually make you any fitter. By setting realistic goals, we relieve their pain, and give them a better chance to succeed.

This is also true for behavior challenges. Many students are physically unable to stay quiet for an entire period. We need to help them set goals for ‘minutes of quiet,’ or ‘interruptions per class.’ Then, we can gradually work towards our expectation.

The other way to meet students where they are is through scaffolding. This is when we provide support to help students meet behavioral or academic expectations.

Disruptive students often act out without realizing it. If we view their behavior as an inability to meet expectations, we shouldn’t get angry. Instead, we should help them reflect on their challenges and help them improve.

I meet with these students, outside of class time, and ask how I can help them respect our norms. Some need a break every 15 minutes. Others like a secret reminder that their peers won’t notice: “When I rub my temple that means I need you to settle down.”

An often overlooked way to support our students is by planning engaging, student-centered lessons. Let’s be honest: the traditional lesson plan structures (‘I do, We Do, You Do,’ or ‘I talk, you take notes’) do little to honor the way kids learn. It leads to behavior problems because students are bored or overwhelmed. Simply planning inquiry-based or workshop-style lessons can go a long way to helping our students succeed. (For more on creating workshop-style lesson plans, read this article.)

Like the encouragement strategies, most support strategies work the same for in-person or online classes.

While I value all of the PRESTO strategies, I do have a soft spot for trust and ownership. These offer the most long-term benefits. And they become even more important during online learning.

Another way to think about intrinsic motivation is alignment. When our work is aligned with our personal goals and beliefs, we love what we do. And we are more successful than when we simply ‘go through the motions.’

But there’s a catch. We may think we want our students to be self-motivated. But we really want them to be self-motivated to do what we want them to do.

Almost half of students in the US have experienced one or more instances of trauma by the time they turn 17…These students often do not see authority as benevolent.

That’s why the whole spectrum is important. There are some things that we must require of our students. They need to become literate and numerate. They can’t use inappropriate language in video chats. And they can’t prevent their peers from learning.

The transitional strategies provide a foundation for nudging students towards intrinsic motivation. And we need not abandon the rules that help our classes function. Once we’ve established a culture of encouragement and support, we’re already on the path toward trust and ownership.

When students trust you, they are motivated to do what you ask of them, simply because it’s you who asked. When they own their learning, it’s you asking them what they need to do to be successful.

In education, I define trust as “a student’s belief that we have their best interests at heart.”

Some students trust us from day one. And as long as we treat them with respect we can keep their trust.

Others make us earn it. The difference comes down to a belief in the “benevolence of authority.”

I had the privilege of growing up in a safe, stable environment. I never knew hunger or experienced violence in my community. My parents were kind and supportive. They still are.

I trusted that the adults around me — parents, teachers, police — were good, honest people who wanted me to succeed.

But educators need to recognize that this is not the reality for many of our students. Almost half of students in the US have experienced one or more instances of trauma by the time they turn 17.

Some feel unsafe in their homes or neighborhoods. Some have been neglected or abused by adults in their lives. Others are under intense pressure from overbearing parents. Or they’ve had negative relationships with teachers in the past.

These students often do not see authority as benevolent. If we begin the year with a heavy-handed, “don’t smile until Christmas” approach, we can trigger them into defensiveness or defiance. The more we assert our authority, the more they resist.

Instead, look to establish trust. Tell them you value them and you believe in them. Say ‘please’ and ‘thank you.’ Remember their names, their hobbies, and their favorite musicians.

Once you earn their trust, keep it by honoring commitments. Be kind, even when you’re frustrated. Make time for 1-on-1 conversations. If you think you’re laying it on way too thick, you’re probably doing it just right.

The final step in the process is handing over ownership of learning to our students. This is no easy process. Don’t expect to check it off the list in a month or two.

Over twelve years of teaching, maybe 10% of my students actually took this level of ownership over their learning.

There are many barriers to student ownership. But the biggest is changing our perspective as teachers. Most students don’t choose to enroll in our classes. Is it reasonable to expect that they should all define success the same way we do?

When I taught high school English, one of my students, Jeongyoon, was an English language-learner and an amazing painter. But she struggled to understand Thoreau and Shakespeare. Let alone write essays about them.

She knew I loved Hemingway. And for her final project, she painted a portrait of ‘Papa’ and insisted I keep it. It hangs in my office to this day.

This student had taken ownership of her learning. She demonstrated emotional intelligence, empathy, and creativity. And though she wasn’t successful by the standards I thought I was supposed to measure, she helped me realize my definition was too narrow.

For the first time that year, she managed to earn in A in the fourth quarter. But more importantly, she changed my perspective on all my future students. I still tried to get my students excited about what I was excited about. But I also looked for ways to measure and value what was important to them.

Eventually, Jeongyoon graduated from business school and earned a master’s in art management. She’s now the head of marketing for an international interior design company. And I was worried about a few run-on sentences…

To give students ownership, it means we must release some control. It means letting them establish rules and norms. Giving them a say in what they learn and how they learn.

This shift is rarely comfortable. As a teacher, I always felt the need to be in control of my class. At the time, it seemed reasonable. But looking back, I think it held my students, and me, back.

It’s not that our need for control isn’t just some egocentric fixation. Teachers experience enormous pressure to cover content, fill our grade books, and ensure our students are safe, happy, and productive.

Giving up control means risking our ability to fulfill our basic responsibilities as teachers. But I will say that things have a way of working out.

Every year in the classroom, I was less controlling than the year before. And by year twelve, my students worked harder ,and learned more, than any of my students had in prior years.

If you’d like to give your students more ownership of their learning, we’re here to help.

Learn more ways to motivate students online by register for an upcoming Online Classroom Management workshop.

Or, you can start right away, by downloading our free Reflective Teaching Guide. It contains profiles of reflective teachers who have taken ownership of their personal growth. There’s also a self-reflection and a goal-setting guide to help you take charge of your professional growth.

The Reflective Teaching Guide will help you develop your vision of the teacher you want to be. And our instructional coaches can help you get there. Schedule your first session today!

GET YOUR FREE GUIDE TO REFLECTIVE TEACHING

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Staying calm in the classroom is one of the most important skills a teacher can have. How do some teachers always seem to keep their cool?

Do the benefits of recess transfer to the classroom? It appears that increasing recess in school can produce surprising benefits.