Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

How much do you trust your textbooks? Many of us rely heavily on our textbooks to tell us what to teach, how to teach it, and when. And with good reason. Unless we want to create all of our materials from scratch, teaching the textbook might seem like the only option.

And textbooks can provide a valuable service. They’re designed to save us the time and frustration of wading through lengthy and confusing standards. We rely on the textbook writers to go through the standards with a fine-toothed comb, anticipate the questions our students will face on state assessments, and break it all down into easily digestible lessons, exercises, and assessments.

But teaching the textbook carries a number of hidden risks. Textbook writers are humans, just like you and me. They have to come up with creative and effective teaching strategies for constantly-shifting standards. All on a deadline. It’s no surprise that some of the lessons in our texts leave us scratching our heads.

And even great lessons from our textbook may not be right for our population. They may go into too much depth on one topic, and not enough on another. Ultimately, it’s up to us to decide what to keep, what to supplement, and what to skip.

First, I should point out that I avoid using the word “curriculum” when talking about a textbook. Referring to a textbook as a curriculum is a uniquely American habit. And a misleading one at that.

It’s a testament to the power of textbook makers that so many educators are willing to refer to a mass-produced publication as our curriculum.

A curriculum is a plan for learning. One that should be based on the distinct features of each school: your schedule, your students interests and proficiency, and the unique talents of your teachers.

A textbook can be a useful tool in creating that plan. But it should never be your only resource. Knowing your standards and creating custom curriculum plans are the first steps to ensuring you get the most out of whatever resources you’re using.

Are you ready to go beyond ‘teaching the textbook,’ but not sure where to start? Schedule your FREE CONSULTATION today to learn how Room to Discover can support you with all of your curriculum planning needs.

When I began teaching, I never really questioned whether I was teaching standards or teaching a textbook. In fact, during my first five years, I never even looked at the standards.

The word sounded so important, so official. Standards. I imagined they were composed by doctors of education and signed into law by governors and presidents. They were none of my business at any rate.

Someone would just give me the set of books for the course I was to teach, and I’d work my way through them as best I could.

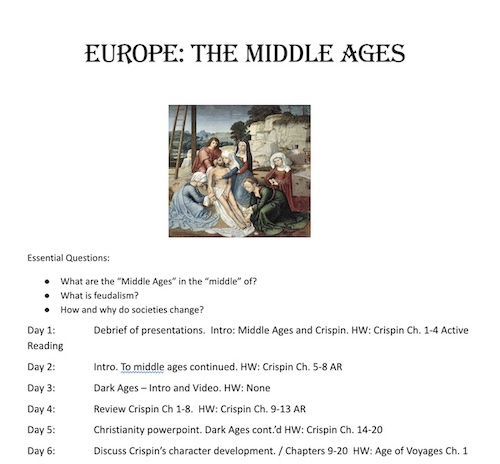

Then one year, towards the end of summer break, my department chair asked me for my curriculum plans. My what?

“You know, the schedule of what you’re teaching this year and when and how you’ll be addressing each standard.” I felt like Jim Halpert, when Charles Minor asked him for a “rundown.” I hadn’t thought past the first two weeks of school, and now I had a week to plan my entire year!

But as stressful as this experience was, it was one of the most beneficial professional learning experiences of my teaching career. Yes, I spent a lot of time digging into standards, and creating a detailed overview of every unit I would teach that year. But the time I invested was just a fraction of the planning time I saved throughout the year.

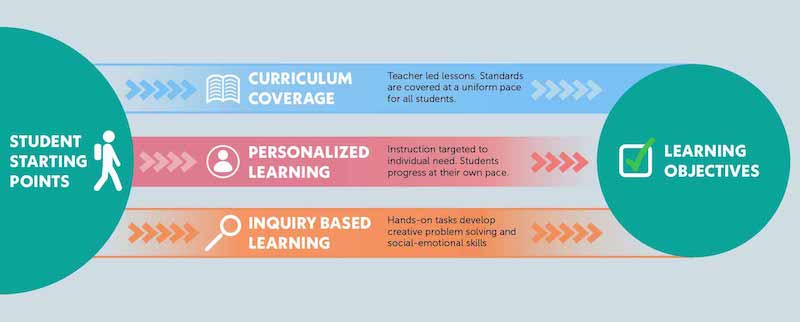

More importantly, I instantly became a better teacher. I moved away from focusing on what I needed to “get through,” (content coverage) to where we needed to “get to” (student achievement). I was able to incorporate more inquiry-based learning, which kept my students engaged, and developed their conceptual understanding.

I was also able to tell where my students were, relative to grade level standards, which helped me to differentiate my approaches to better meet their needs.

The curriculum planning workshops I now facilitate are designed to replicate this process in a more methodical, and less stressful, way. Teachers who have completed the workshop report similar results, from increased confidence in their content, and hours of saved planning time every week throughout the school year.

Despite the limitations of teaching the textbook, many schools still default to such an approach to curriculum planning.

Textbook producers are experts in presenting their product as a quick and easy solution to whatever ails your school.

Many educators will talk about how they are “Adopting a new math program.” Words like ‘adopting’ and ‘program’ make this sound like an intensive and meaningful process. But it often just means buying a new textbook.

As with most things in life, the easy fix rarely gets the job done. According to a 2019 study by Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research, our choice of textbook has little impact on student outcomes.

Meaningful change comes from building school culture and developing teacher expertise. Such initiatives take time and hard work, and may even require outside expertise.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that you shouldn’t use a textbook. But it means that whichever one you use, you need to build curriculum plans that are customized for your school.

Here are four reasons to be cautious of treating your textbook as your curriculum plan.

Most schools have around 180 school days. So if you’re a textbook publisher, you’ll want to make sure you have at least 180 lessons. Better yet, why not make it 200 just to be safe?

In reality, few teachers will need more than 100 lessons for a year-long course. Some lessons take more than one day. Some periods are lost to assemblies, snow days, pandemics, and so forth. Besides, you won’t be teaching every single lesson from the text. Right?

I’ve come to believe that the content for most grade level courses can be taught in 30-40 high-quality inquiry-based lessons. But who would buy a textbook with just 30 lessons?

So publishers include everything they can think of: multiple lessons on the same topic, pages and pages of repetitive exercises, suggested enrichment and differentiation strategies.

And when teachers receive these massive textbooks, we feel we have to “cover” all of it. We end up rushing through the content or skipping lessons, ensuring many students will be lost.

When we create custom curriculum plans, we can choose only the lessons that are most critical in addressing our standards. This allows us to move at a reasonable pace. We can even build in time for differentiation, enrichment, inquiry-based learning, and so on.

In theory, standards describe the “minimum” level of mastery students should have at each grade level.

But in reality, the vast majority of US students are below grade level in math and reading. The latest National Assessment for Educational Progress, a study by the US Department of Education, concluded that a mere ⅓ of students are proficient in grade-level reading.

And the NAEP math data is not much better. It shows that only 40% of 4th grade students are proficient in grade level math. And by 8th grade, that number drops to 34%.

In other words, our “minimum standards” are more like hopes and dreams. But textbook publishers must play along with the pretense that most students are on or above grade level.

It’s possible that your students are reading and doing math exactly on grade level. But for the rest of us, curriculum planning helps to ensure that your instruction is designed for your students. This often means dedicating time to content from prior grade levels, or incorporating personalized learning for remediation or acceleration.

For deep learning to occur, students need to understand the connections between the different concepts they will learn throughout the year. This connection is what is meant by coherence.

Indeed, coherence tends to be the biggest sequencing challenge in planning a curriculum. That’s because standards are meant to be milestones. To assess student mastery, we have to break bigger concepts into smaller, measurable bits. For example, when assessing reading, we need separate measures for fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and so on.

But learning is a holistic process, which is why standards make poor learning objectives. For conceptual learning to occur, teachers, students, and curriculum plans, all need to be clear on how the pieces fit together to form a meaningful whole.

Students become better writers by reading. They are better at division when they see how it connects to multiplication and repeated subtraction. And this is where textbooks tend to come up short.

Sequencing is also an important part of establishing coherence. It helps to start the year with engaging topics, and to give students an overview of the topics they’ll learn. It also makes sense to teach follow-up review and foundational topics with the more advanced concepts they support.

Yet the sequencing of many textbooks makes the content feel dry, disconnected, and confusing.

A striking example comes from 8th grade math. Most books start the year with Scientific Notation. I can hardly think of a better way to convince students that math is boring.

Instead, why not start with highly engaging topics, like functions and geometric transformations? These standards also provide a conceptual backbone for most 8th grade content. Why not use one of these to bookend the course?

Every teacher I know supplements their curriculum in some way. It’s how we put our mark on our classrooms. I loved using debate as a way to teach expository writing.

Others incorporate music, art, or technology projects to help their subjects come to life. These projects engage students, and teach skills like collaboration and problem-solving.

And while many texts are now addressing inquiry-based activities, it’s still hard to find a text that does a great job of it. These types of learning experiences work best when teachers draw on their passions and personal experiences.

But many teachers struggle to find the instructional time (not to mention the planning time) for hands-on and student-centered learning. In order to introduce projects into our curriculum, we need to skip some things.

Careful planning is required to leave time for hands-on learning, while ensuring we don’t skip important foundations and core standards.

Educators who see the connections between their lessons and their standards are more effective than those who only experience standards second-hand, via their textbook.

The former are able to communicate the ‘big picture’ ideas to their students, create engaging problem-based lessons, and better meet their students’ individual needs.

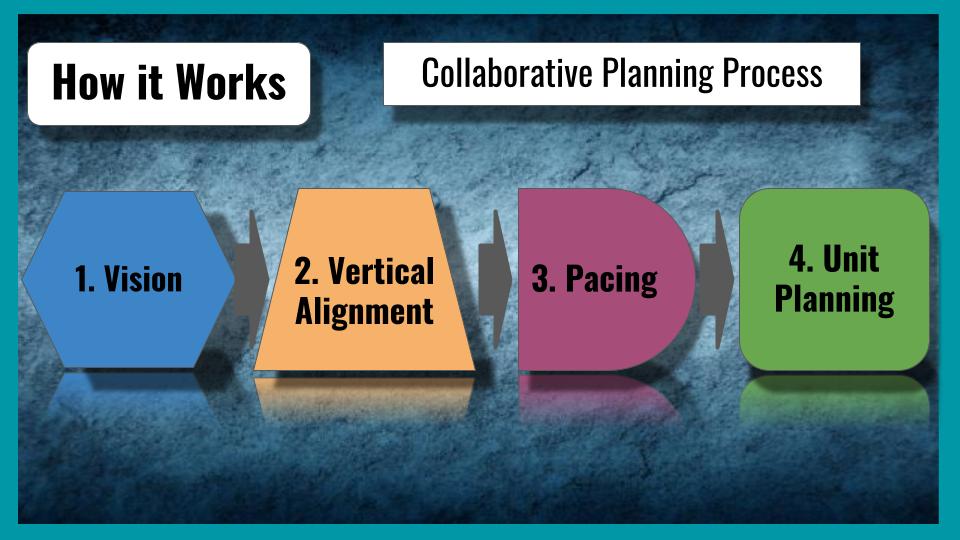

That’s why our approach to curriculum planning is a collaborative process. Our curriculum specialists engage both teachers and administrators in a four-stage process to ensure your curriculum meets the needs of your school or district.

As with most things, the hardest part about curriculum planning is taking the first step. I hope this post has given you some helpful ideas on how to get started.

If you’re ready to bring the benefits of high-quality, customized curriculum plans to your school or district, schedule a free consultation with one of our curriculum specialists.

We’ll help you decide on an approach that best meets the needs of your school. And we can help you find the right resources and support to ensure you reach your curriculum planning goals.

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Does the Danielson Rubric improve teaching? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, it’s a rubric, not a training program. But…

Effective curriculum plans are built by engaging teachers in a collaborative, school-based process. Getting a head start before summer break is key.