Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Every classroom teacher remembers a time when we lost our cool. That day we didn’t get enough sleep, had a headache, or simply hit our limit. Those also seem to be the days our students decide to act out and push our buttons. Whatever the reason, at least for a moment, we lose the ability to stay calm in the classroom.

For many new teachers, staying centered and calm in the classroom is a daily challenge. Over time, most of us learn how classroom management and mindfulness can help reduce the emotional ups and downs.

But some teachers have a magical ability to maintain calm in the classroom, no matter the circumstances. I’ve often wondered how they manage to stay cool and collected even when students are bouncing off the wall.

It’s possible that such emotional control is something that you’re born with. Maybe you just have it…or you don’t. But as an educator trying to maintain a growth mindset, I like to think that anything can be learned.

Step foot in any classroom, and you can tell right away if you are in a calm place.

In some rooms, students are listening intently, working quietly, or actively engaged in collaborative learning.

But in other classrooms, something just feels off. The noise level might be the same. Students might even be seated quietly. But instead of a calm productive buzz, there’s a tension. The teacher holds tightly on the reins, afraid that the minute she lets go, the whole class will devolve into chaos.

You might not notice anything different about their teaching practices. But there’s something different about the culture in these classrooms. In one room, students have taken ownership. They know that “in this room, we do things this way.” In the other, the teacher is on constant alert, monitoring and correcting every disruption and off-task behavior.

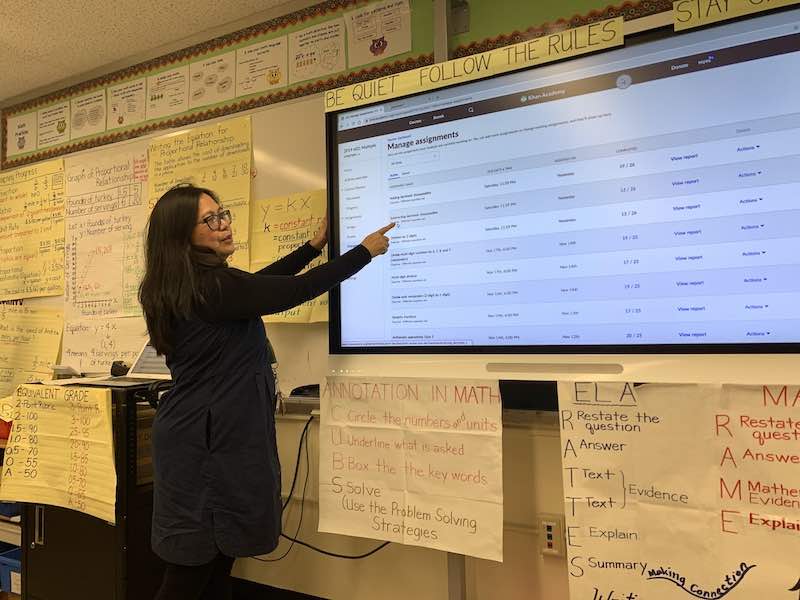

A few years ago, I had the chance to visit the first type of class. Mary Yee, a 7th grade math teacher in Brooklyn, has a surprisingly effective (and unconventional) way of addressing behavior issues.

Ms. Yee’s school serves a diverse population of low-income students, many of whom face hardships most of us will never know.

As I watched her students enter the room, most sat down and cleared their desks. Ms. Yee greeted them and handed-out computers to most of them.

But one student, Martin, stood behind his chair, backpack on his desk. Ms. Yee passed him by, handing a computer to the next student. Martin protested, “That’s not fair!” Ms. Yee calmly reminded him of the expectation, and continued distributing the devices.

Despite the gentleness of the reminder, it sparked a full-blown melt-down. Martin raised his voice and stomped around the room. He called Ms. Yee names I won’t repeat, and threw his bag on the floor.

Ms. Yee barely seemed to notice. At first, I couldn’t believe she was letting this behavior go unaddressed. What would the other students think? Wasn’t she sending the message that this was acceptable?

But then, something surprising happened. The other students stepped in:

“Martin, you’ll get your computer if you just sit down.”

“Do you need to do this every day?”

“Can you please just clear your desk?”

The next thing I knew, Martin was sitting down and ready to work.

Martin was looking for a battle. At first, I worried that Ms. Yee was ignoring the problem, or didn’t know how to respond. But she was addressing the issue in her own way, sending her students the message that calm in the classroom began with her.

I sat down with Ms. Yee to learn her formula for making behavior issues magically disappear.

While calm in the classroom feels natural to her now, it wasn’t always so easy. She was recruited to teach in New York in 2004, during a teaching shortage. Before that, she taught at a Catholic School in the Philippines.

“In my old school, my students started each class with their hands folded on the table. When they were working, you could hear a pin drop. I could even walk down the hall to use the bathroom, and they would still be working when I came back.”

Teaching in New York presented a great economic opportunity, but it wasn’t without surprises. “Many of my students behaved poorly. Others complained that they couldn’t focus with so many disruptions.”

“One of my students told me, ‘You need to yell if you want them to listen.’”

She started raising her voice and found that it worked — at first. But eventually, “I was yelling every two minutes. It didn’t change their attitude or impact their long-term behavior.”

“I didn’t feel right about yelling all the time. Besides, it didn’t really work. I still faced one interruption after another.”

In her third year, she had the chance to work with an instructional coach who specialized in classroom management. “My coach encouraged me to reflect on my teaching. After each lesson, we would talk through what worked and what didn’t.”

“I realized that addressing behavior during the lesson wasn’t working. My coach encouraged me to build relationships with students by talking with them outside of class. I could ignore the students who were running around the room, and continue teaching the students who were paying attention.”

Ms. Yee started to realize that empathy was the key to staying calm in the classroom. When students are disrespectful, she doesn’t take it personally. Instead, she asks herself, “what is the real reason the student is acting out?”

“Most are just looking for attention. A student once told me, ‘By the time I get home, my parents are sleeping. They’ve been working all day. And when I wake up in the morning, they’re already gone.”

Parental involvement has proven benefits for a students’ education. But low-income families face unique challenges in providing such support.

Ms. Yee acknowledges their need for attention, but without reinforcing the negative behavior.

“During the whole class lesson, I ignore them and continue what I’m doing.” Later, during small group work, she comes back to connect with the student who acted out.

“Since other students are working in groups [link], you can talk to them without the whole class watching. And you can hit two goals at once. Once I address their emotional needs, I can also support them academically.”

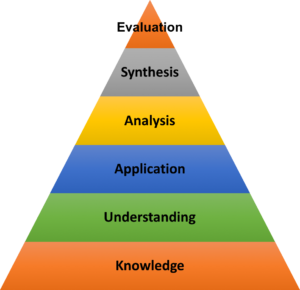

Her approach is supported by research. Many educators are noticing the importance of “Maszlow before Bloom.”

Benjamin Bloom studied the importance of conceptual learning, while Abraham Maslow focused on the hierarchy of needs. His research showed that students can’t focus on academic learning when their biological and emotional needs aren’t met.

“Many teachers see classroom management as ‘us against them.’ Either I win and the class is orderly, or my students win and it’s chaos. But we need to take a student-centered approach. It can’t become a battle where one person gets their way. Students need to have their needs met, or the class won’t work.”

Ms. Yee believes that any teacher can learn her strategies for bringing calm to their classroom. It begins by considering student perspectives.

“I look back to when I was a student. We’ve all passed through the stage of adolescence. Even if our experience is not exactly like theirs, we need to look for ways that our journeys are similar.”

The first step to meaningful growth is reflection. By thinking carefully about our teaching practices, we can take ownership of our growth as educators.

Start by reading the Guide to Reflective Teaching. This free resource includes self-assessments, planning guides, and other helpful organizers. Completing the guide will help ensure that you can manage your classroom, and give your absolute best to all of your students, every day of the week.

You can also develop classroom culture by incorporating social-emotional classroom management strategies. Learn how to bring these strategies to your classroom in our online workshop, A Social-Emotional Approach to Managing Behavior. Register today to save your seat!

Mrs. Yee is a 22 year veteran educator at John Ericsson Middle School 126 in Brooklyn, NY. Before teaching, she worked for seven years as a chemical engineer, but it wasn’t until she began teaching that she truly felt inspired. She believes that the purpose of education is to learn from our mistakes: “Teachers need to embrace the same growth mindset we expect from our students.” You can find her on Twitter at @HearYee3

Mrs. Yee is a 22 year veteran educator at John Ericsson Middle School 126 in Brooklyn, NY. Before teaching, she worked for seven years as a chemical engineer, but it wasn’t until she began teaching that she truly felt inspired. She believes that the purpose of education is to learn from our mistakes: “Teachers need to embrace the same growth mindset we expect from our students.” You can find her on Twitter at @HearYee3

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Does the Danielson Rubric improve teaching? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, it’s a rubric, not a training program. But…

Looking for a simple way to identify effective teaching? Consider how you (or your team) are performing in each of these three critical domains.