Addressing The Problem with Homework

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

When the pandemic hit and school buildings shut down, few educators were focused on grading online learning.

We had bigger fish to fry. And it wasn’t fair to our students. “How can we hold them accountable when we can’t support them in the way we used to?”

As the months went by and schools remained closed, we could no longer just fill time until things went back to normal.

As long as schools remain closed, we owe it to our students to ensure they receive the best education possible. And that means producing some evidence that learning is still happening in our classes.

Most schools began by suspending grading altogether. When grades returned, schools across the country experienced an alarming increase in failure rates. Before we saw these results, most of us were worried about the cheating that might occur during online assessment.

It seems the bigger problem is that many students aren’t even bothering to cheat. Or that online learning has simply been too disorienting, leaving students unable to succeed.

It appears that the end of widespread online learning may be in sight. Some schools have returned to in-person instruction. Others are moving to hybrid instruction. There is an argument for just pushing through until we can forget about online learning.

But I believe there are good reasons to solve the problem of grading online learning. For one, there’s no guarantee that online learning will go away. What if a new strain can bypass the vaccines? Or another emergency forces schools to close again.

But even without another extended school closure, we should find a better online grading solution. After all, if we can find a grading system that helps engage students when learning online, wouldn’t such a system be even more effective for engaging students when they return to our classrooms?

The truth about grading online learning is that the challenges aren’t new.

Our existing grading system does little to motivate students. In fact, our current system is more of a barrier to student success. Top performers can succeed with little effort. For struggling learners, even with great effort, high grades feel out of reach.

Grades have also been shown to magnify inequities along the lines of race and class. For one, upper class parents can exert more pressure on schools to drive grade inflation. And wealthier students are more likely to have access to more academic support from their parents. Wealthy parents tend to be more highly educated. And they’re more likely to work jobs that allow them to be home in the evening, providing support with homework and studying.

Any teacher can tell you that grading adds significantly to teachers’ workload. This prevents many teachers from maintaining a healthy work-life balance. And ever minute spent grading is a minute not spent planning engaging lessons or building relationships with students.

The shift to online learning has simply turned up the volume on all of these problems. Students who were already challenged academically, now have a host of technology obstacles to contend with. And as parents’ role in schooling has increased, students living in poverty are disproportionately affected. These students also have less access to high-speed internet and updated devices.

Teacher workload has become so overwhelming during the pandemic, that teachers are leaving the profession in record numbers.

As problematic as these challenges are, they are not the root of the problem with grading. They are just the symptoms.

The underlying problem is one of purpose. Why do we grade our students in the first place? Is it to motivate them? To help parents understand their progress? Or is it so admissions officers can more easily rate and sort our students?

Each of these purposes, and audiences, warrants a different approach. But we’ve never really decided which is most important. So instead, we focus on what’s easiest to measure. And we use grading systems that shoot for the middle, and serve no purpose particularly well.

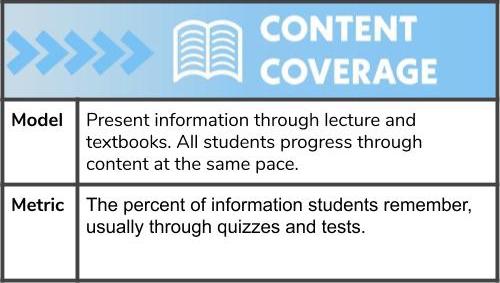

One way to improve grading is to focus on the Three Bridges of Learning. In a traditional system, students move through grade-level content at a fixed pace. Their grades are based on how much of that content they can reproduce on a test.

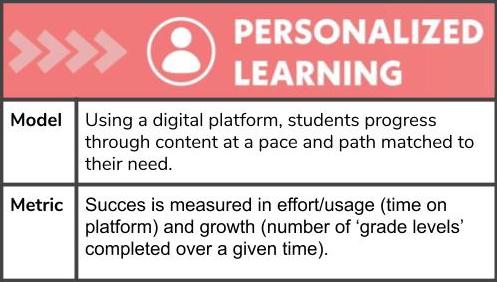

But in a 3-Bridges model, remembering grade level content is just one indicator of learning. Students also have the chance to build skills in a way that targets their individual needs. This is the second bridge, personalized learning.

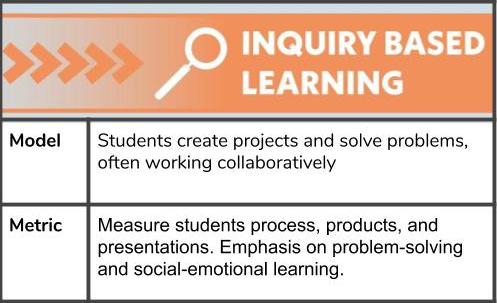

The third bridge, inquiry-based learning, consists of hands-on learning experiences. Students learn to work productively with peers, and apply what they learn to solve interesting and challenging problems.

Each bridge has its own methods, and its own measures of success. In most grading systems, we ask teachers to differentiate instruction, and to provide opportunities for collaboration.

However, our grading systems still focus almost exclusively on content coverage. As a result, the other bridges are “nice to have,” but not essential. And since they’re not part of our core assessments they usually just get pushed to the side.

Basing grades on all three bridges provides more students an avenue to success. It challenges top performers to deepen conceptual learning and apply what they know. And it does wonders to increase student engagement among all students.

These changes are incredibly helpful during in-person instruction. But during remote learning, they’re absolutely essential.

Content coverage is the coin of the realm in modern schools. It is the model of learning based on delivering information  to students and finding out what they’ve remembered. It’s the philosophy behind textbooks, standardized tests, and “I do, we do, you do.”

to students and finding out what they’ve remembered. It’s the philosophy behind textbooks, standardized tests, and “I do, we do, you do.”

The curriculum coverage model works like this: Each course consists of certain information, or ‘content.’ The teacher’s job is to ‘cover’ the content by presenting it to students.

Later, we measure student success by the percentage of questions they get right on a unit test or state test.

This model makes it easy to compare students and provide reports to outside institutions. But it falls short in many other ways. The assessments are not very useful for motivating students. Or for helping them understand their progress.

The second bridge, personalized learning, is similar in terms of what students learn. But it takes a very different  approach to how they learn, as well as how we measure learning.

approach to how they learn, as well as how we measure learning.

The personalized learning model matches instruction to student need. Just because a student is in a 7th grade class, it doesn’t mean she needs to read the same books or solve the same equations as her classmates. We use technology to understand student strengths and needs, and to assign work that is right for them.

Since each student is learning different material, we don’t expect uniform outcomes. For a PL initiative to be successful, students need to take ownership of their learning by setting and working towards their own goals.

The metrics of success in this model include effort and growth. We can measure and grade the time spent using an adaptive platform. Eventually, we can measure their growth in ‘years of progress.’ If a student makes more than one year of academic progress in a school year, it’s considered a successful year, and warrants a strong grade.

With the first two bridges, though the pace and path are different, we are still focused on remembering information. But with

inquiry-based learning, we are focused on students’ ability to apply their learning, solve challenging problems, and collaborate with peers.

Students also acquire content knowledge along the way. But a good task allows each student to learn different things from the same activity. So rather than measuring achievement with ‘objective’ assessments, like tests, we measure performance in terms of process, product, and presentation.

When students collaborate, communicate, and maintain focus, they earn points for process. When they create an impressive artifact, they earn points for their product. And when they present these artifacts or describe their learning to teachers and peers, they earn points for presentation. I use a group work rubric to let students know what’s expected, and to provide feedback on all three categories.

It’s true that these metrics aren’t as easy to assess as multiple-choice questions. And it’s not always easy to find high-quality tasks, especially for online learning. But I’ve had a lot of success using Interactive Google Slides to drive online collaboration and student engagement.

In live schools, most of our grades come from assessing Bridge One learning goals. But these are the most difficult to measure in an online setting. In many ways, they are also the least meaningful measures of learning.

To simply and effectively grade online learning, you’ll want to include measures of personalized learning and inquiry-based learning. My hope is that once we incorporate these measures, we’ll also bring them back to the classroom.

Here are some practical tips for incorporating a Three Bridges approach into your grading. Each tip will help make your online grading simpler, friendlier, and more effective.

One of the best favors you can do yourself as a teacher is to think weekly, rather than daily.

It’s not always easy! A content coverage approach requires that we keep all of our students on the same page. We don’t have room for one student to fall a few days behind, while another moves a few days ahead.

But this approach is both limiting and inefficient. In an online setting, it becomes nearly impossible for students to keep up with daily assignments. And it’s just as challenging for teachers to keep track of every student on a daily basis.

As a result, we’re forced assign work that is fast to complete and easy to grade. But such work is also less interesting and meaningful.

Giving weekly assignments lets students work around their own schedules. The independence gives them more ownership of their learning. It also saves us time grading assignments and chasing down missing work.

If you use a personalized learning platform like IXL or Khan Academy, simply assign a number of minutes per week. I recommend 30-60. Divide the number of minutes completed by the number assigned to find their weekly grade.

You can also assign a group activity, like a story analysis or a number proof. These fun and engaging tasks demand deep thinking and collaboration. Students can work on their own schedules over the course of a week, and present to the group the following week. Use a rubric to grade students on their process, product, and presentation.

No products were found matching your selection.

To grade students fairly, we need to be clear on why we’re grading them. Is it for them? Their parents? Our administration? Is it for us?

Of course, it’s a little bit of each. But shouldn’t the students come first? And shouldn’t we try to build our students up by giving the highest grades we can?

I know, I know. Sometimes it can be really difficult. A student blows off an assignment. Or disrespects us on Zoom. It can feel like grades are the only tool we have to assert our authority. But that power can also be dangerous.

When I first started teaching, I had a reputation as a tough grader. I thought that grading conservatively would make my students try harder, and they’d rise to the challenge.

But over time, I realized that grading was consuming too much of my time and energy. And it was straining my relationship with students and their parents.

Every year I spent in the classroom, I became a more lenient grader. And guess what? Each year, my students worked harder and learned more than the year before. I found the motivational power of strict grading to be an illusion. I later found that my experiences were confirmed by research.

Do everything you can to ensure your students’ grades are high. When students see you as their ally, they’ll spend less energy trying to work the system, and more time living up to the potential you see in them.

This one’s a bit controversial, but I think we get too hung up on the accuracy of our grades.

On one level, it makes sense. We want grades to be fair. We feel that the students who are best in our subject should get the best grades.

Accuracy is most important when reporting to an outside audience. But for motivating our students, accuracy can actually be counter-productive. Students who do well with little effort get rewarded for their complacency. And students who struggle, despite working hard, get frustrated and give up.

Grades can be a powerful tool, if we use them as such. I think of grades as a down payment. Most of us don’t have enough cash in the bank to buy a house. But the bank still lets us live there, believing that over time, we’ll pay the balance.

The same should go for our struggling learners. Give them a grade that reflects their potential. Let them know that you expect them to live up to the grade you gave them.

And make sure your easy-going high-performers have room to grow. They may be used to seeing their grade as a comparison to their peers. But to be motivational purposed, they need to start seeing their grades as a comparison with their best self.

The unit test. The day of reckoning. After focusing on a topic for weeks or months, test day is the time for students to show what they know.

As educators, we tend to see the unit test as the most objective and reliable measure of learning. We watch our students take it, so we can be sure they didn’t receive help. And there’s an answer key, so we can be sure the right answers are right and the wrong answers are wrong.

But just because something is easy to measure doesn’t mean it’s useful, or relevant to students’ future success.

I can’t think of any job where success is measured every few weeks with a test of memory. Success in our jobs depends on what we accomplish. And it’s is measured by all the little things we do, day in and day out.

Unit testing certainly serves a purpose, but that purpose is exaggerated and distorted by our current system. And with distance learning, we can’t even say that unit tests are the most accurate form of assessment.

Instead, grade students on their productivity. If you are using a personalized learning platform, grade them for time on-task. Eventually, you can factor in their progress.

For inquiry-based tasks, look at artifacts. These give us a more authentic measure of their productivity. It’s also easier to tell when a student has done their own work, especially when they present their work to the class.

There are countless ways to make our grading systems more effective and efficient. But trying to do them all will just leave you overwhelmed.

As you adjust to grading online learning, make changes in small steps. Even small changes may feel sudden and dramatic. So go easy on yourself. Expect to make mistakes, and try to learn from them.

If you’ve already been using personalized or inquiry-based learning, the shift will be a bit easier. Our group work rubric can help with grading inquiry-based tasks. And our personalized learning plan will help your students set their goals, and help you track their progress.

For a complete menu of our services and downloadable resources for online learning, visit roomtodiscover.com/online. There you can reserve your seat in an upcoming online workshop or schedule a custom online workshop for your school. You can also connect with an instructional coach who will help you work through your biggest challenges with content, pedagogy, or technology.

Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter to stay up-to-date on our latest articles, videos, and print resources.

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Jeff Lisciandrello is the founder of Room to Discover and an education consultant specializing in student-centered learning. His 3-Bridges Design for Learning helps schools explore innovative practices within traditional settings. He enjoys helping educators embrace inquiry-based and personalized approaches to instruction. You can connect with him via Twitter @EdTechJeff

Many educators are starting to recognize the problem with homework. And while homework is almost universal, there is little evidence that it actually works.

Does the Danielson Rubric improve teaching? Maybe it’s an unfair question. After all, it’s a rubric, not a training program. But…

Teaching word problems takes more than key words. The Polya Process helps your students think strategically and make sense of story problems.